Assisted suicide is legal in nine states – California, Colorado, Hawaii, Maine, Montana, New Jersey, Oregon, Vermont and Washington – and the District of Columbia. California’s law is currently being challenged in court but is functioning during that process. Oregon was the first to legalize assisted suicide, in 1997, and its law serves as a model for other states seeking legalization.

Legislation that has been approved in the states calls for the individual to be at least 18 years old, have a diagnosis of a terminal condition with six or less months to live, and be a resident of the state. Two physicians must be consulted before an individual is approved for assisted suicide. If a psychological or psychiatric condition – such as depression – is indicated, the individual is usually referred to a mental health professional. If the individual is determined to be clear of a psychological or psychiatric condition, they may proceed with obtaining the lethal prescription.

Supporters of assisted suicide often call it “medical aid in dying” or “death with dignity.” The process sounds simple and straightforward. Yet it’s not, as is discussed below.

The drug most commonly prescribed for assisted suicide is the barbiturate secobarbital. When used to treat insomnia, the typical dose of secobarbital is 100 milligrams in capsule form. When used for assisted suicide, the dose is 9 grams – or 9,000 milligrams – in capsule form. That translates into 90 times the usual dosage, or 90 capsules.

The drug most commonly prescribed for assisted suicide is the barbiturate secobarbital. When used to treat insomnia, the typical dose of secobarbital is 100 milligrams in capsule form. When used for assisted suicide, the dose is 9 grams – or 9,000 milligrams – in capsule form. That translates into 90 times the usual dosage, or 90 capsules.

Also prescribed is a combination of four drugs known as DDMP: diazepam, digoxin, morphine sulfate, and propranolol. Another combination of drugs is DDMA, made up of diazepam, digoxin, morphine sulfate, and amitriptyline.

Individuals also take an antiemetic about an hour before ingesting the fatal dose to prevent nausea and vomiting.

The time span from drug ingestion to death can last as short as one minute or as long as 47 hours, according to the 2019 annual report on Oregon’s law.

The Oregon report shows that individuals participating in assisted suicide are overwhelmingly over 65 years of age (75%), white (96%) and well-educated (53% had at least a bachelor’s degree.)

The three top concerns leading to a decision to participate in assisted suicide have long remained the same: decreasing ability to engage in activities that made life enjoyable, loss of autonomy, and loss of dignity.

Notably, pain and how to control it ranks sixth out of the seven concerns listed, with only 33% of those participating in assisted suicide mentioning it.

Consider the following:

Dr. Brian Callister, a Reno, Nevada-based internal medicine specialist and associate professor at the University of Nevada-Reno School of Medicine, has told multiple media outlets of two patients whose insurance companies denied coverage of standard, life-saving medical procedures but offered life-ending drugs used in physician-assisted suicide.

California resident Stephanie Packer was diagnosed with scleroderma at age 29. Chemotherapy slows the progression of the chronic autoimmune disease that causes scar tissue to form in her lungs.

Medical diagnoses of terminal conditions are not always correct, which is why patients are always encouraged to get a second opinion.

A ground-breaking October 2019 report on assisted suicide from the National Council on Disability (NCD) recounts the example of Jeannette Hall, an Oregon resident who was diagnosed with cancer in 2000 and told she had six months to a year to live. She asked her doctor about the state’s assisted suicide law, but he encouraged her not to give up. As of the time of the report’s publication, she was alive and well – 19 years later.

Individuals living with a physical or developmental disability often face oppressive cultural values characterizing the need for help as undignified or burdensome to others. The option of assisted suicide only exacerbates those feelings.

The National Council on Disability report notes the work of Carol Gill, Ph.D., professor emeritus in the department of disability and human development at the University of Illinois at Chicago, who succinctly sums up that fear: “How can one provide safeguards for that?”

Gill also recognizes the tendency to equate disability with burdensomeness is pervasive in today’s society, and the NCD report notes a striking passage from a 1994 article on patient requests to hasten death from the Archive of Internal Medicine:

“Symptoms and loss of function can give rise to dependency on others, a situation that was widely perceived as intolerable . . . : ‘I’m inconveniencing, I’m still inconveniencing other people who look after me and stuff like that. I don’t want to be like that. I wouldn’t enjoy it, I wouldn’t. I wouldn’t. No. I’d rather die.”

(Susan D. Block and J. Andrew Billings, “Patient Requests to Hasten Death: Evaluation and Management in Terminal Care,” Archive of Internal Medicine 154, no. 18 (1994): 2039-47)

Offering assisted suicide to a supposedly terminal and depressed individual only preys on that person’s struggle to attain mental health.

Offering assisted suicide to a supposedly terminal and depressed individual only preys on that person’s struggle to attain mental health.

The same National Council on Disability report mentioned earlier tells of 62-year-old Michael Freeland of Oregon, who struggled with depression most of his life before learning he had terminal lung cancer. He asked for assisted suicide and was given a prescription without any sort of psychological evaluation.

But he then reached out to Physicians for Compassionate Care, a medical group dedicated to improving the care of seriously ill individuals without assisted suicide, and was put in touch with a volunteer trained in counseling and referred to another doctor. He chose to get treatment for his cancer, and received help with pain management and other personal problems. He lived two more years, eventually dying of natural causes.

Assisted suicide easily lends itself to so-called “doctor shopping,” in which patients seek out physicians – and mental health providers, when necessary – who are sympathetic to their request. The 2019 report on Oregon’s law bears this out: The median duration of the patient-prescribing physician relationship was 14 weeks, or 3 ½ months.

Once prescribed and picked up by the patient, the lethal drugs are not subject to any additional scrutiny. If patients change their minds about going through with the suicide, they still have possession of the drugs, leaving the pills to fall into the hands of random individuals and children. Of the 290 Oregon residents who received a prescription in 2019, 170 ingested the deadly drugs that year, while 18 more took drugs prescribed in previous years, according to the 2019 report on Oregon’s law.

Nearly all medical schools require their students upon graduation to take some sort of pledge to uphold professional ethical standards as a healer. Assisted suicide wreaks havoc on that oath.

Additionally, assisted suicide laws protect physicians and others from all criminal and civil liability if they provide lethal drugs based on a “good faith” belief that statutory criteria are met. That is the lowest culpability standard possible, even below that of negligence, which is the minimum standard governing all other physician duties.

Assisted suicide asks doctors to disregard what is perhaps the most universal moral injunction – do not kill. An op-ed in the Jan. 19, 2016 issue of the Journal of the American Medical Association, which was dedicated to the topics of death, dying and the end of life, poignantly states the obvious:

“Insofar as physicians enjoy societal trust, it is because since Hippocrates, physicians have maintained solidarity with those who are sick and disabled, seeking only to heal and refusing to use their skills and powers to do harm. That is why Doctors without Borders treats injured Taliban soldiers. It is why physicians have refused to participate in capital punishment, or to be active combatants, or to cooperate with torture. It is why physicians have refused to help patients commit suicide. “

(Y. Tony Yang, ScD., LLM., MPH and Farr A. Curlin, MD, “Why Physicians Should Oppose Assisted Suicide,” Journal of the American Medical Association, Volume 315, no. 3 (2016): 247-8.)

When assisted suicide becomes socially acceptable through legalization, suicides in general increase.

The National Council on Disability report notes that before Oregon legalized assisted suicide, its suicide rate was similar to the national average. However, by 2010, Oregon’s suicide rate was 41% above the national average.

Further, a 2015 article in the Southern Medical Journal found that states with assisted suicide laws are associated, on average, with a 6.3% increase in total suicides. For individuals older than 65, the increase was 14.5%.

An op-ed published in The Washington Post a month later by Aaron Kheriaty, associate professor of psychiatry and director of the medical ethics program at the University of California Irvine School of Medicine, noted the unsurprising results of the study.

“You don’t discourage suicide by assisting suicide … publicized cases of suicide often produce clusters of copycat cases, often disproportionately affecting young people, who frequently use the same method as the original case.”

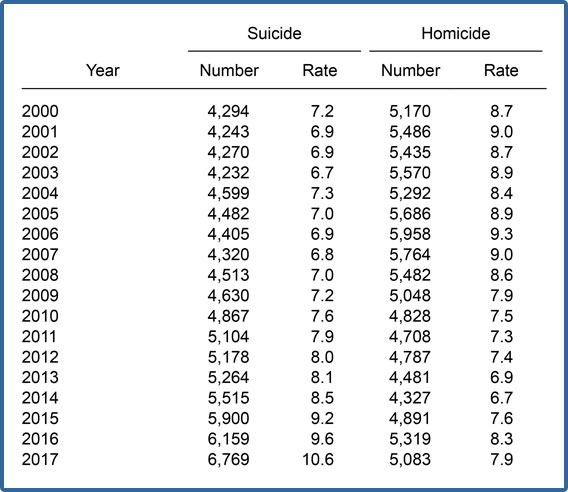

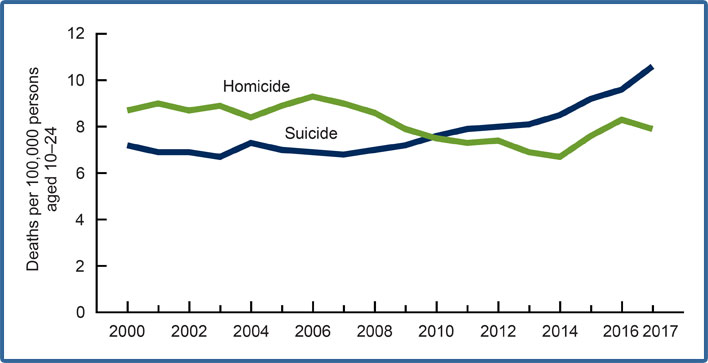

And this comes at a time when the suicide rate in the United States increased 33% from 1999 through 2017, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Since 2008, suicide has ranked as the 10th leading cause of death for all ages. Suicide also ranked as the second-leading cause of death for ages 10-24 in 2017, the most recent year for which data are available. Shockingly, the suicide rate among those aged 10-24 increased 56 percent from 2007 and 2017.

If people you know appear to be considering suicide, please let them know of the National Suicide Prevention Hotline of 1-800-273-8255, which offers free, confidential support 24 hours a day, seven days a week.

Suicide and homicide death rates among persons aged 10-24; United States, 2000-2017

(Rates are per 100,00 population enumerated as of April 1 for 2000 and 2010 and estimated as of July 1 for all other years.)

NOTE: Rates are per 1000,000 persons aged 10 – 24.

SOURCE: National Center for Health Statistics Data Brief No. 352, October 2019, “Death Rates

Due to Suicide and Homicide Among Persons Aged 10-14: United States, 2000-2017″

https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db352_tables-508.pdf#1

Suicide and homicide death rates among persons aged 10-24: United States, 2000-2017

SOURCE: National Center for Health Statistics Data Brief No. 352, October 2019, “Death

Rates Due to Suicide and Homicide Among Persons Aged 10-24: United States, 2000-2017,”

https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db352-h.pdf